Written by Katerina Parsons (SALTer working in Tegucigalpa with MCC Partner, Asociación para una Sociedad Más Justa)

November 7, 2015

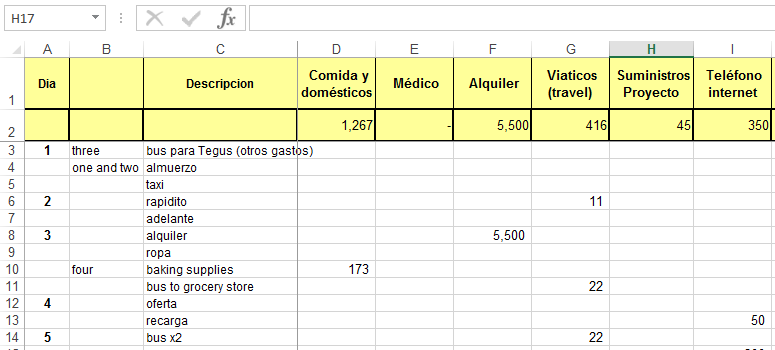

It’s the end of the month, so I’m going over my budget and making sure everything is accounted for. Every purchase I’ve made all month is meticulously recorded, receipts are duly labeled, photographed, and filed in a manila folder. It’s tedious work. My spreadsheet rarely comes out right. I don’t like doing this.

My friends, family, and church donated generously through Mennonite Central Committee so that I could work here at the Association for a More Just Society, and through MCC all my expenses are paid – rent, food, transportation – as long as they’re all properly documented in my Excel sheet. Sometimes I wonder, when I enter my daily fifty-cent bus fare, whether this is all a little bit much.

But there is a reason for this sort of attentiveness, however time-consuming. In fact, I’m becoming convinced that these are the details that matter about an organization, that these records and audits and due process, as unsexy as they might seem, are actively bringing about justice.

“Transparency” and “accountability” are the mantras here in an organization that spends most of its time making sure that the government works as it’s supposed to. It’s an uphill battle. No one thinks that they’re a crook, especially not people who have been unchallenged their whole lives. No one thinks they need the sort of accountability that exhaustive documentation provides.

Certainly a few corrupt people exploit regulatory gaps to steal millions of dollars or threaten others’ lives. But most people’s corruption looks a lot more tame. It’s clocking in twenty minutes before you actually start to work. It’s failing to get a signature. It’s signing off on something you didn’t actually do, because you’ll get to it eventually.

It’s not that any of those minor infractions breaks a system, but the culture it creates, the balance of risks and rewards it shifts, starts to strain a system to its breaking point.

The Association for a More Just Society (AJS) is Transparency International’s local chapter here, and last year signed a landmark agreement with the Honduran government that charged them, as civil society, with monitoring the transparency and anti-corruption efforts of major government ministries.

That’s how I found myself from the first day elbows deep in the Honduran Education System’s Purchasing and Contracts protocols. I translated graphs of compliance percentages and documentation delivered and began to realize why people say that the Devil’s in the details.

You can’t talk about justice on a big scale without talking about justice on a small scale. You can’t talk about education reform without making sure that it’s recorded whether your teachers actually show up to teach their classes.

Take health – Honduras is one of the poorest countries in Central America, and approximately 70% of its population depend on publicly-funded hospitals for all their medical care. Yet too often they’re sent home without desperately-needed medicine to treat illnesses from heart disease to schizophrenia because the hospitals don’t have the necessary medicines in stock. When I visited the hospital, doctors talked about buying extra sutures with their own money for the times when the dispensary ran out mid-surgery.

There are two ways to respond to this system that isn’t working as it should. One could create supplemental medical brigades, donate medicines from abroad and send foreign doctors, form health nonprofits or give low-interests loans to purchase medicines on the private market. Or one could go to the source, the Ministry of Health itself, and start to ask questions about why it isn’t working like it should.

Transformemos Honduras, a program of AJS, did the latter, sending request after request for the sort of official documentation that would help them see how medicine purchasing was being managed. Though Honduran law says the information should be delivered within ten days, they waited six months, during which time these justice fighters probably didn’t feel very much like heroes.

When what documentation there was began to come together, it told a bleak story. The Ministry of Health wasn’t analyzing the market to see how much medicines should cost, and it wasn’t following the purchase contract process in the way the law laid out. That meant it was paying double, triple, even seven times as much for medicines as it should. What’s worse, the companies themselves were involved in writing the purchase orders, telling the Ministry of Health what medicines it should purchase instead of the other way around.

The already-strained Ministry of Health was overpaying for medicines that weren’t even necessarily the ones that were needed. Even worse, some of these medicines were never delivered, while others were delivered in unacceptable quality – after audits started, auditors found some medicines infected with bacteria, while others were delivered with only four of their 11 essential ingredients.

The story gets even worse – the warehousing government medicines was run by a woman who appeared to use the stash as her personal piggybank, forging medicine orders and selling the excess, mismanaging the disorganized warehouse so that expensive pills were left to spoil while people in hospitals died for lack of drugs.

In 2013, Transformemos Honduras presented their report, which was numbers and percentages and all the little pieces of methodology that sometimes seem unimportant. The effect was electric. The Honduran government immediately removed the director from her position. She, along with other wealthy, powerful people would eventually face consequences — caught in their corruption by a missing trail of paperwork.

It’s not always fun or exciting to sift through hundreds of spreadsheets or file the government forms that will give you access to hundreds more. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t worth it. We need to realize that investment in “unsexy” work like social audits and performance reviews is foundational to creating systems that serve the most vulnerable well, and that transparency and accountability aren’t just buzzwords, they’re building blocks to better systems.

Working at AJS, I’m empowered to be a part of civil society’s oversight of government systems. But transparency and accountability touch my own life as well. It matters that I account for the money I spend, that I’m willing to be as open with my use of others’ funds as I want the government to be with their’s.

So I stare at the expense column in front of me. I write my daily 50 cents under the appropriate column in my expense spreadsheet, hit save, and then hit send.