Christopher Fretz works with MCC Mexico in San Cristobal. This article was originally published on his personal blog.

Today is October 2. As a parent, this date will always remind me of the beauty and pain of being a parent who struggles to pass my commitment to justice and peacemaking onto my children while also protecting their innocence.

Christopher Fretz

Every day on the way to taking my girls to school, the bus we take passes the faded mural shown above. It was originally just a jungle scene with a lion. But then someone added the text, which says “October 2 will never be forgotten.” It is the date of the Tlatelolco massacre, in which Mexican police and soldiers opened fire on student protestors in the Plaza de Las Tres Culturas in the Tlatelolco section of Mexico City in 1968. What exactly happened still isn’t entirely clear, with estimates on the number of students killed ranging between 30 and 300.

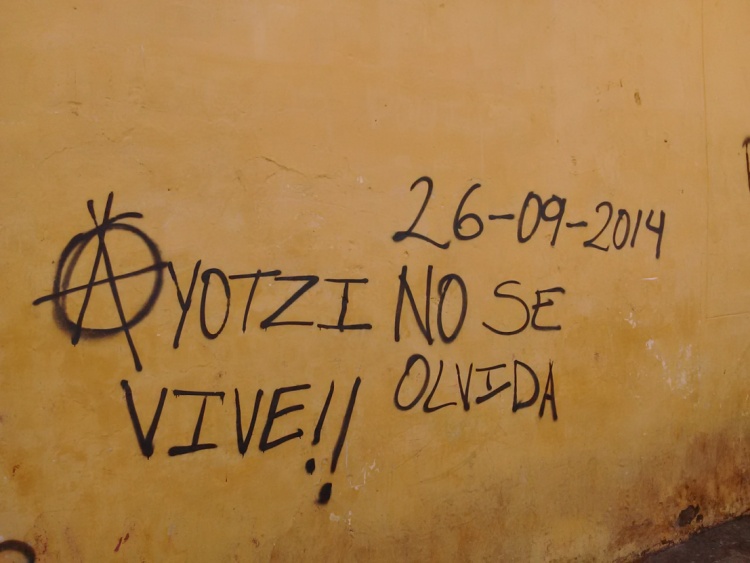

Recently other murals and graffiti have started popping up around San Cristóbal like the ones below. They are commemorating the 2-year anniversary of the disappearance of 43 studentsfrom Ayotzinapa on September 26, 2014 in Iguala, in the state of Guerrero, Mexico. Their disappearance is widely believed to have been a mass kidnapping carried out by the Mexican military and/or some level of government.

English translation: Because we have memory… we miss the forty-three. Christopher Fretz.

As a dad, it’s hard to know when and how to talk about these situations of violence and injustice with my daughters, but as I learned a year ago, sometimes children intuitively know what to focus on in situations of injustice.

October 2 fell on a Friday last year, and it was the opening weekend of a pizzeria that Lindsey’s co-worker was starting downtown. Lindsey had a workshop that afternoon, so the girls and I set out on our own to visit the pizzeria. One of my co-workers had explained the history of the Tlatelolco massacre a few days earlier, but it hadn’t occurred to me that it was the anniversary. As we walked through the market, we came across a big march to commemorate the massacre. Of course those marching also took the opportunity to protest the disappearance of the 43 students from Ayotzinapa.

As they chanted about “Los 43,” as they’re known in Mexico, Ramona asked me what they were yelling. Ramona can be pretty sensitive when it comes to people hurting each other, but I decided that this is the kind of thing she might end up hearing from other people anyway, so I braced myself for her reaction and told her that there were some students that had been killed and that the people were sad and angry about it.

English translation: Ayotzi will not be forgotten. Live!

I was already feeling pretty sad and vulnerable as I listened to the protesters, but I almost lost it when Ramona instinctively knew what was most important to focus on. “What were their names Poppa?” she asked. “What were the students’ names?” I felt tears forming in my eyes, and I did my best to keep from weeping and told her that I didn’t know their names, but that I could find them out later for her if she wanted. I was amazed at how she knew that naming the students and remembering who they are is essential in violent situations of uncertainty and loss.

We went to the pizzeria and had a calm, relaxed dinner together. Afterwards, Ramona never asked me again about the students’ names, but that afternoon has stuck with me. It’s one of my experiences here that has had a deep impact on me. I continue to ponder how much to protect our girls from all the heartbreak of the world, or whether, at least to some extent, we need to let them feel that heartbreak. My hope and prayer is that as parents we can accompany them as they experience the pain and heartbreak of injustice, and that experiencing it will transform them into women who are deeply committed to restorative justice, compassion, and reconciliation.